1.4 Stakeholder Engagement Strategies – The Carrot or the Stick?

1.4.1 Definitions

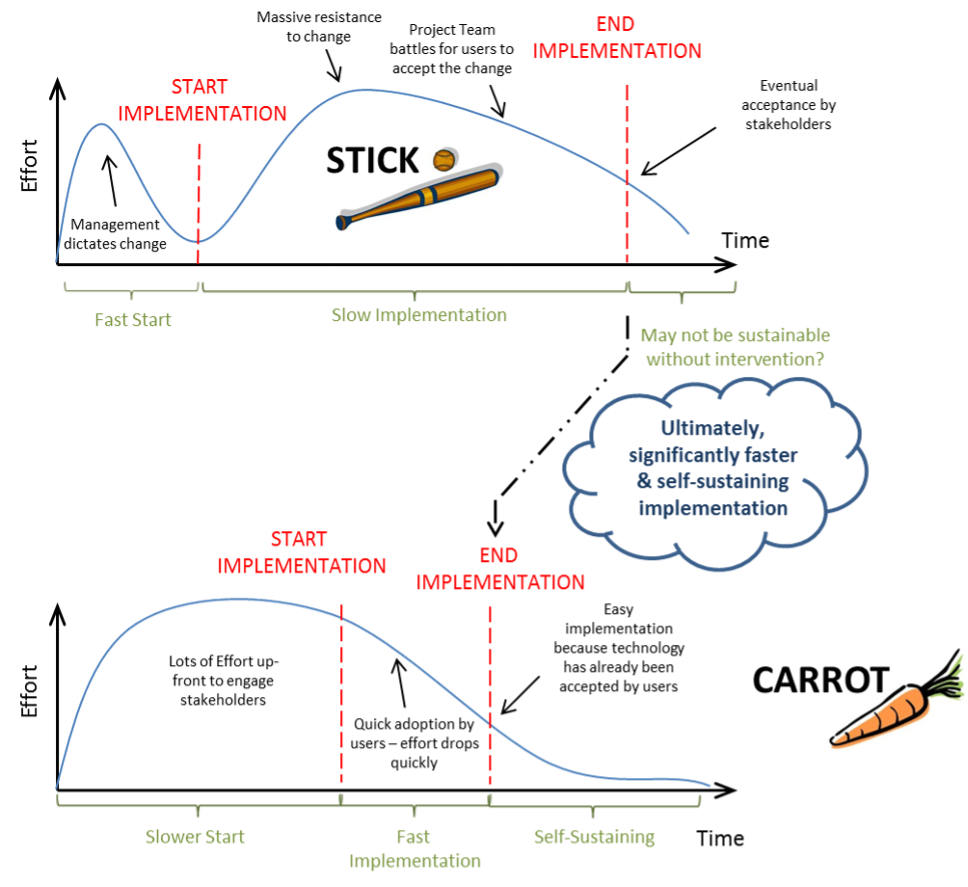

There are 2 conflicting strategies around Stakeholder Engagement – one that ENFORCES a technology onto users (The Stick) and the

other that tries to make users DESIRE the technology (The Carrot).

Figure 1, below shows some typical comments associated with each engagement strategy when stakeholders are questioned about a

new technology that impacts their job – this is consistent with any change and the more intrusive the proposed technology is regarded

then the greater the separation of positive versus negative comments that are heard.

It is obvious that the Stick approach elicits negative, fearful thoughts that show mistrust in the company. On the other hand, the Carrot

approach usually encourages more positive thoughts and might even produce volunteers for the change on occasions!

It is easy to decide that a project to introduce a new technology should adopt the Carrot Engagement Strategy and generate a positive,

voluntary, inclusive atmosphere, but is there actually a benefit to the business and how does a project leader go about it?

1.4.2 Implementation Cycle

Figure 2, below shows the typical life-cycle of a technology project depicted as effort vs. time. It can be seen that the Stick approach

quickly moves to implementation (since it is basically directed by management that it will be done), but then it meets massive resistance

to change by the users (who fear the technology, might believe that the Company is using it to discipline them, or maybe do them out of a

job, and it is likely that the union is advising employees to refuse to participate in – or help – the project). The project team will then battle

with users for a long time, until eventually the technology will probably be accepted – possibly after threats of disciplinary action and / or a

lot of time and effort has been spent.

Unfortunately, if the project team does not stay engaged right until the end, the change may not have been adequately embedded and the

change may not be self-sustaining – this can usually be seen a few months or years later, when the technology has been left in disrepair,

is no longer used by the business or has been replaced by a different technology solution that is really a duplication and unnecessary

cost.

Implementing Technology in the Mining Industry

(Overcoming Adoption Barriers)

I wrote this document somewhere around 2015. I recently (2024) came across it again and was interested to read my thoughts from that time. I think almost nothing has changed in the mining industry when it comes to adopting technology (unfortunately). Take a look, see what you think and please let me know if you find any of this useful!

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Purpose

This document provides a model for the introduction of technology within the mining industry. It is well understood that key to successful

introduction of any change is a combination of a number of factors, including: cultural fit, stakeholder engagement, leadership support &

financial benefit – and that without ANY ONE of these, the change is doomed to fail.

The primary objective of this document is to develop a generic set of guidelines that can be used by any mining business when

introducing a new technology, however the guidelines are likely to be just as useful for introduction of ANY change, specifically:

Safety – The statutory, legislation, Risk Management processes, corporate expectations and industry standards associated with

introduction of new technologies.

Costs – Including up-front funding of research, site trials, capital purchases, operating expenses and ongoing support. This also

captures the short-term impact as a result of the change – for example, lost production as a piece of equipment is taken out of

service for a length of time in order for the new technology to be installed and commissioned.

Acceptance – Gaining the support of stakeholders and overcoming negative perceptions about change including threats to jobs.

Success – Ensuring realistic performance objectives are set and then delivered.

1.2 Background

This document has been written over many years whilst I worked (and usually struggled) to successfully implement new technologies into

the mining industry. I learnt that resistance to chance is exists right throughout the industry – whether at Head Office, the General

Managers’ office or at the ‘coal face’.

My biggest learning however was that “resistance” is generally not towards the proposed technology itself, but more that the individual

does not have a reason to PERSONALLY support the change – I call this the “what’s in it for me?” factor.

Most mining companies group technology projects into 3 timeframes:

0-3 years “incremental improvement now”

3-8 years “next”

8+ years “new”

The focus of this document is predominantly on “NOW” and “NEXT” technologies – by their definition, “NEW” technologies are far into the

future, and will not likely have any impact on today’s operations. It is the impending introduction of technology – and specifically the

IMPACT on the site and site personnel that this model will address.

1.3 The Basics of Implementing Change

In its’ simplest form, implementing technology is no more than change management, with the added complexity of the uncertainty that

comes with a technology that may be unproven in an operating environment or for which the payback period may be many years after the

initial investment.

Thus, it is worthwhile examining the basics of successful change management first, and then address the specific nuances that are

associated with technology and the mining industry.

It is critical to understand that successful change management is more complicated than simply introducing a good idea. This simplistic

view ignores the important human aspect of influencing success.

It has been suggested that the success of a proposed change can be represented by the following simple equation:

“The effectiveness (E) of any improvement initiative is a function of the quality (Q) of the technical strategy adopted, multiplied

by the acceptance (A) of that strategy by the organization. E = Q * A”

In other words, a Successful Change must not only provide a technical solution to some problem or need that works, but it must also

be Accepted by the people which it impacts.

If we can assume that the technical quality of the technology is proven; and will work as expected, then the real key to a successful

change is to gain acceptance – this is done through STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT.

The Carrot approach, on the other hand takes time at the start of the project to engage the stakeholders – to get them on board with the

new technology and work towards a much smoother and quicker adoption once it is implemented. Thus, the start may be later, but the

end is much sooner as the technology is accepted much quicker and more likely to be self-sustaining.

Sadly, it is the author’s experience that most change projects implemented at coal mines adopt the Stick approach – they start quickly,

meet massive resistance and take a very long time to be accepted – if they ever really do at all.

It is proposed that the Carrot approach is ALWAYS the best strategy and will deliver the best results for the business in the long-term.

The remainder of this document explains how to successful adopt this approach - what resources are required for such a strategy, tools to

assist the project leader and some of the mistakes to avoid.

1.4.3 Appropriate use of the Stick!

STICK TO THE CARROT APPROACH – Encourage users to want to be part of the solution; but

DON’T BE AFRAID TO USE THE STICK WHEN APPROPRIATE. Any change will have at least one “Saboteur” – that is, people who take

action prevent the change being successful. Whilst this document proposes that the carrot approach of engagement and getting people to

buy into the change is ALWAYS the most successful in the long-term, managers should not forget they have the authority to introduce

such change.

Thus, if one or two individuals are being disruptive to the point that they are impacting the project negatively and stopping it from

succeeding, and assuming they have been given sufficient time and opportunity to “join the bus” so to speak, then it is APPRORIATE

AND NECESSARY for the manager to step in and take action against those individuals.

1.5 What’s so special about implementing new technology in a mining context?

This document might be titled “Implementing Change” – however it has been written specifically to address the implementation of new

technologies in the mining industry.

So what is so different about mining technology from ‘traditional’ change management? The answers are: TECHNOLOGY and

CONSEQUENCE.

Firstly TECHNOLOGY - new technology inherently introduces more risks than most other types of changes. For example, a ‘traditional’

change management project might deal with introducing a new working roster for employees – such as a 5 day per week, 3 shift

workplace moving to 7 day, 24 hour operations. Whilst this sort of project introduces significant change for the employees and company,

it does not introduce any new ideas and the solution is well understood and demonstrated successfully in many industries and other

companies.

A new technology change project on the other hand will likely introduce a technology that has almost certainly not been proven within the

organisation and possibly not even within the industry within which that organisation operates (ie Surface Coal Mining).. It is possible that

the technology may NOT EVER have been proven in any commercial environment. In these cases, it is easy to understand that the

introduction of technology can introduce a whole raft of additional risks and perceptions that will make it more difficult to be successful

than a non-technical change such as a new working roster.

Many recent advances in mining technology have focused on the move towards automation of certain stages of the production process

and there is a gradual move towards full autonomy – where people are removed almost entirely from the mine operation. Clearly this will

cause uncertainty from the existing workforce with respect to job security – hardly a motivator for them accepting a new technology!

Secondly the CONSEQUENCE of failure associated with mining is BIG - everything to do with the mining industry has high stakes and on

a grand scale, including equipment size, 24 hours per day, 365 days per year production pressures, stress of stakeholders, continuous

working hours and safety expectations. Thus, when mistakes are made, or if things don’t go quite right the consequence is usually

greater than other industries.

Thus, these consequences often lead to a culture of conservatism within the mining industry, which inevitably makes support for

introduction of change more difficult.

Summary of forces acting against the introduction of new technology into a mine operation:

• Dominant union in the industry – against differentiation of individuals and see introduction of technology as a risk of job losses.

• Fear by some stakeholders of changes to job roles as a result of the technology

• Uncertainty of success of an unproven technology

• Risk averse culture due to:

o High consequence from failure (costs, production)

o High Safety standards (do not tolerate safety risks)